“That’s outgoing, right?”

We’d heard the booms from the moment we’d arrived in the village. The dull blasts rang from somewhere over the lip of the hills that cradled the valley, mingling with the rattling of passing cars and the laughter of children, playing in their yards. The sounds kept no predictable rhythm, sometimes firing just once before falling silent, sometimes chasing one after the other in a determined patter.

I knew it was artillery, having heard the same sounds since I’d arrived in the region five days before, though never so loudly as in this village, a few kilometres from the front-line city of Chasiv Yar. War music, I thought. Donbas thunder. The American medic leaned against the van, took a drag off his cigarette, and nodded.

“Yeah,” he said. “That’s outgoing.”

Comforted, I squatted in the shade thrown by the van, a mobile dental clinic donated by a Slovak charity, and took stock of the surroundings. That day, I was tagging along with a medical team from the grassroots humanitarian organization Road 2 Relief, for a project whose final form is still taking shape; after a lurching 90 minute drive out of the group’s base in Sloviansk, we’d come to the village, tucked in a valley between two of Donetsk Oblast’s most brutalized cities.

It was a beautiful place, in the verdant and folksy way of eastern Ukraine. Green fields were bracketed by lush copses of trees. Dogs trotted freely down the rutted dirt street, past worn wooden fences and sprays of yellow and pink flowers, blooming in planters made from old tires. We’d parked in front of a neatly-kept brick building which served as the village’s heart. Outside, a silver-haired woman sat at a folding table, surrounded by paperwork and plastic bags of donated food aid. Villagers trickled in and out of the building, nodding at us in friendly but perfunctory greeting.

“Dobry den,” they mumbled, as they passed.

Suddenly, a sharp crack split the heat-heavy air. Not too close, but not too far either. I jerked my gaze to the west, from where it had come, and felt a tightness gripping my guts, as if my liquified stomach was being squeezed towards my lungs.

The medic sucked his cigarette. “That’s incoming.”

This was new to me. Feels bad, I thought. But the birds kept chirping, and the people outside the village office kept chatting, and none of them seemed to care, very much. After over a year of such terrible music, I knew, I’d start to tune it out too.

— — —

The war is fake, did you know that? It is, in fact, the fakest war ever. It’s not real, just a media fiction, created by Western governments and the shadow-people running the world in order to control the population. (One need not bother asking to which ethno-religious group these alleged shadow people belong; this type of conspiracy only ever points one direction.)

I was informed of the fakeness of the war one night last week, on Twitter, while I was lying awake in my bed in a rented studio apartment in Sloviansk, a small city situated just 35 kilometres northwest of the unbearable hell of Bakhmut. When I’d checked in that afternoon the landlady, a bubbly middle-aged woman with flamboyantly artificial lips and bleach-blonde hair, cracked saucy jokes in Russian as she showed off a fridge stocked with fake caviar and contraband champagne. I guessed that, when she bought the cozy apartment and decorated it in an ornate navy-and-gold nautical theme, she’d imagined hosting guests coming in for a relaxing day of salt mud baths at the popular Sloviansk spa resort. But that resort was bombed last year; now, her renters are mostly soldiers’ lovers, come to steal a few amorous hours on the war’s bitterest edge.

So while the apartment’s canopied bed could double as an X-rated movie set, it was a pleasant place to pass my long, lonely nights in Sloviansk. Wartime curfew falls early, that close to the front; after 9 p.m. there was not much to do but browse social media, serenaded by the comforting whirr of the electric fireplace and the booms of outgoing shelling. It was my first time hearing mortars being fired, and I was surprised by how little it bothered me: “It’s always nice to listen to our own artillery, rather than enemy shelling,” a soldier friend texted. Silver linings, I guess.

And on these long, boring nights — the middle of the afternoon, in North America — I found myself delving deep in rabbit-hole discussions about Ukraine on Twitter. The site has become increasingly chaotic since Elon Musk took over and, under the guise of “free speech,” slashed its content moderation. Near any conversation about global events is now swiftly besieged by commenters bearing disinformation, conspiratorial allegations and naked antisemitism; but few topics attract them more surely than the war in Ukraine, and it’s from those commenters I learned the war isn’t real.

Fake. Fake. Fakest war ever. It’s never clear what this means: do they literally believe there is no combat, no blood splattering the streets of flattened Bakhmut, no dead civilians and no missiles over Ukraine? It’s hard to say. But what these disbelievers are quite clear about is how they know the war is fake.

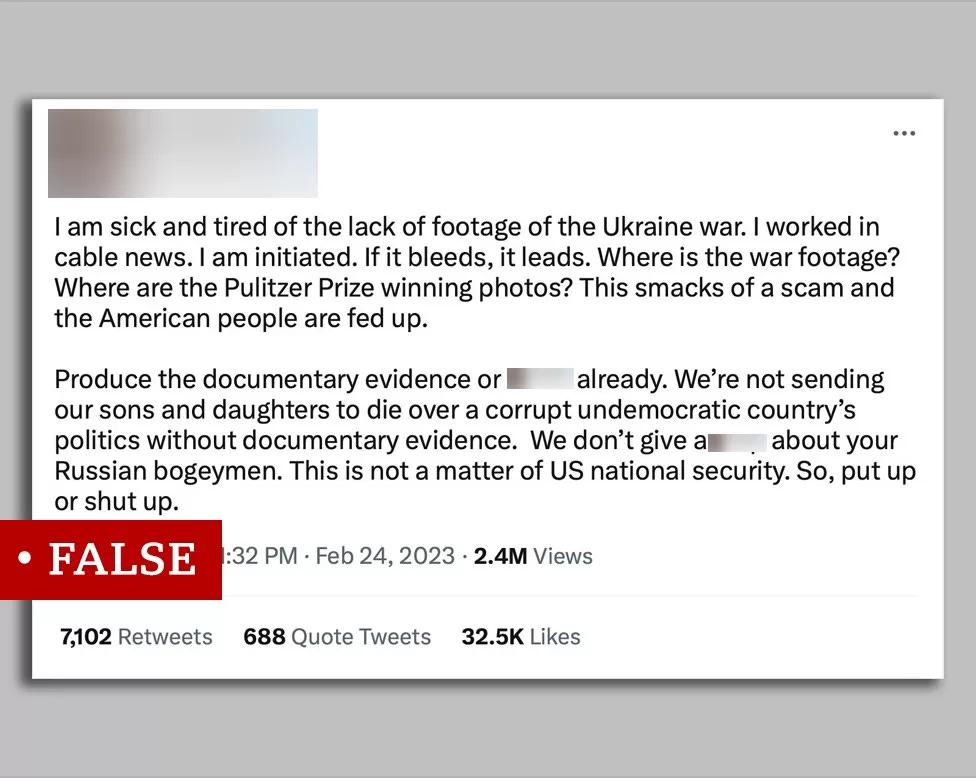

For instance, they know the war is fake because people in Kyiv eat at McDonalds, a video of which set off a frenzy of war denialism on social media last week. (One such example, from Reddit: “I see a lot of fighting age adults… that is not defending their country home land that is supposedly in war.”) They know it’s fake because kids ran for shelter during a daytime missile attack — school safety rules require students go to shelter during sirens — while adults nearby did not. Above all, they know it’s fake because there’s no video or photographic proof of there even being a war, a statement made by multiple right-wing Twitter accounts with large followings.

Of all the supposed proof given that the war is fake, it’s this latter one that’s the most bizarre and, for its sheer break with reality, the most disturbing. This war is easily the most extensively photographed in history. Every day, pictures and videos stream from the front lines and sites of aerial attacks, bearing visceral witness to combat, damage and death. These images are captured by thousands of journalists, countless civilians with cell phone cameras, military drones and GoPro cameras affixed to the helmets of soldiers from both sides. It’s one thing to make a conspiratorial accusation about why fighting-age men still eat Big Macs in Kyiv; it’s outright frightening that someone can be swimming in an ocean of grisly war imagery, while declaring we’re not even wet.

I don’t know how many people are truly seduced by these Tweets; as a percentage, not many. But their constant injection into discussions is exhausting, even just to watch; I have no idea how Ukrainians bear the barrage of accusations that their nightmare is a fiction. I can feel the conspiracies working inside my brain too; not, of course, in the way that I believe them, but in how I can sense myself starting to turn away, to retreat inward, to give up defending the borders of the very concept of truth.

Look, it’s no secret that I’m working through a crisis of faith with journalism, and my role within it. Those doubts come from many directions, and this is one. Opinions are one thing; of course, we expect clashing opinions. But I don’t know how to work in a world where reality itself is under ever-increasing ideological assault. At some point, it’s just too much. At some point, you start to wonder if anything even matters. What is real? What is truth? Fine, fine, I don’t care anymore. Believe what you want.

But that’s the point of the conspiracy theories, though. That’s their purpose. I’m not convinced that most bloviators who call the war fake literally believe that, or care if others do. They have a larger aim, which is to undermine the very concept of agreed truth and overwhelm the structures by which we transmit it. In the resulting social and political chaos and intractable conflict, who will most benefit?

In Sloviansk, the clock crept towards midnight. I turned off my phone, setting aside a dribble of Tweets screaming that the whole war is a ruse, and fell asleep to the booms of distant artillery, drumming rhythms of death.

— — —

The sun that beats down on the village does not pierce Vyacheslav’s windows, does not touch the inside of his house, which is dark and damp and smells of rot. He has lived here a long time, though he does not have much to show for it. In the kitchen, stripped of everything except a rusted gas stove, mould runs down the walls. Debris from Vyacheslav’s life is scattered about the living room, where he sits and eats and sleeps on a divan couch covered by a sheet: empty pill bottles, an old Soviet booklet about Catherine the Great, a wad of cash equal to about $15 CAD.

Vyacheslav is 68, and not in good health. He had a stroke, though he can’t remember when, and his mouth hurts where he’s missing his front teeth. His leg hurts when he sits, he can’t sleep, and he speaks in rants of slurred and stuttered Russian, unable to focus on the questions the translators are asking him.

“Make him sit down,” the medic says, pleading. “I need to examine him.”

It takes some coaxing, but at last the translators get Vyacheslav to sit in silence long enough for the medic, a nurse from Oregon, to strap a blood pressure cuff around the man’s stout arm. They wait quietly as it inflates, serenaded by the low cannonades of outgoing artillery that never truly cease.

“Two hundred over 110,” the medic reads out, in a monotone of practiced calm.

It’s a terrifying number, deep into the realm of hypertensive crisis. In fact, the medic tells me later, it’s close to the highest he’s ever seen in a patient who’s still conscious. But Vyacheslav receives the news with little interest. His mind wanders. Yes, he has medications, but some of the bottles are empty, and he can’t remember when he ran out. His wife left him a long time ago and his daughter doesn’t talk to him anymore. His son, who lives in Dnipro, visits when he can to bring food and help with laundry, but Vyacheslav doesn’t recall the last time that was. April, maybe, or else winter. The translators check his phone; his son hasn’t called for months.

The medic cuts him off, asking the translators to hold the man’s attention. He begins to explain that Vyacheslav needs to go to the hospital in Kramatorsk, about an hour’s drive north and west over pockmarked dirt roads. Vyacheslav grunts. No, no, he says, it’s too far, and when he went to the hospital before, he felt worse.

Somewhere over the hills, an incoming mortar shell explodes with a crack.

Vyacheslav returns to his rambling reveries. The medic excuses himself, and steps out to get a few medications from the van. I find him there, smoking another cigarette. He says little, but a grim-set jaw betrays his frustration; in a way, my heart breaks for him as much as the old man. He has the capability to help, and a sworn duty to provide the best care he can; to be refused that mission, to know the truth but be unable to have it accepted, must be worse than not being able to help at all. But you can’t force a person to live. And you can’t force them to listen.

When the medic goes back in, Vyacheslav has had a change of heart. He’ll go to the hospital with them, he says, but he will not stay overnight. The medic sighs: then it won’t work, he replies. They will want to keep you.

Instead, he tries to rig a system for Vyacheslav to remember his medications. The translators lay out seven sheets of paper, labelling each with the name of a drug in bold Cyrillic letters, followed by a chart of days of the week. They put these, along with boxes of medications, right in front of the television, explaining in slow, loud voices that each time Vyacheslav takes a pill, he will check it off. They’ll visit him again in a week to see how things are going.

Before they leave, the medic tries one last time to change the ending of the story. If you stay here, he says, you will have another stroke, or a heart attack. You will. And you will lie here for hours, or days, and nobody will come for you, and…

“Let me guess,” my Ukrainian friend said, as I recounted the story to him later. “He refused to go.”

Right, I replied. The medic tried everything to convince him. He told Vyacheslav how they’d drive him to the hospital, and drive him back home. How they’d call his son and pay for his prescriptions. Everything would be taken care of, they said, everything that he needed. All he had to do was make the decision. But still, he wouldn’t go.

My friend shrugs. He grew up in this part of Donbas. He knows these villages, knows these people. He knows, in a way I’m only just learning, how generations of hardship imbued them with a resolute stubbornness and a suspicion of the world outside their regions, one which has never brought much hope. To a man like Vyacheslav, the war is just the latest in a lifetime of privations; the only safe place he knows is his village and his home. The medics, my friend suggests, “don’t understand the situation.”

I know, I know, but you have to try, right? You have to try to save his life.

“Seems kind of pointless,” my friend replied.

I’ve said before that Ukrainians tend to be blunt. Mostly, I think, it’s just that the arc of history taught them to name hard truths clearly, where those of us who were lucky enough to learn the world as a softer place would still rather not.

— — —

It’s getting worse, the problem. Did it start with the Moon landing? The Flat Earth Society? I remember when I thought 9/11 Truthers were the height of delusion, but then came QAnon. Either way, a tendency to conspiracy must have been with us all along. Perhaps, in the squalid warrens of Ancient Roman tenements, plebeians told each other that Gaul didn’t really exist, that it was just a myth crafted by Caesar. Or maybe not. Maybe before we could all read and write, before the keys to knowledge itself were freed, people tended to accept what news they received.

Either way, it’s getting worse and more dangerous. Social media enables it. And if this war is the latest stress test for social resilience against conspiracy and disinformation, we’re failing. Because while I’ve learned the war is fake from Twitter, I’ve also learned many other falsehoods about Ukraine there too, most of them much more widespread because they’re less dramatic, and don’t require a near-total rejection of reality.

Every day, those who’ve taken Russia’s side, or at least oppose their own governments’ support of Ukraine, repeat falsehoods about the country and its people. Many of these are certainly troll farm propaganda accounts, sowing suspicion of Ukraine in order to weaken foreign support and inflame political strife in allied nations. (It’s working.)

But it would be a mistake to think all or even most of those who spread Ukraine war disinformation are nefarious actors. I’ve seen friends repeat things that I know to be factually untrue; but they believe those things, and not because they’re paid to do so by the Kremlin. It’s more that, once disinformation is released into the social media wilds, it filters through that ecosystem until it appears to be organic, delivered from people or sources with whom we have affinity, and existing trust.

Sometimes, in private conversations, I’ve been able to correct those misconceptions; my friends, like everyone, tend to more easily accept information that confirms their existing opinions, but they aren’t conspiracy theorists. What I don’t know is how to reach those inching closer to the latter position. It’s surreal to find yourself arguing that things you’ve seen with your own eyes are not, in fact, a government lie.

One night, while lying awake in Sloviansk, I tried to engage with a Canadian man on Twitter, who insisted that there must be no homeless in Ukraine, and that pensioners here were flush with Canadian taxpayer dollars, thanks to a pension increase recently approved by the Ukrainian government.

But there are people sleeping rough in Kyiv; I’ve seen them. And the pension increase Ukraine approved wasn’t done with Canadian money, but through its existing system; a desperately needed relief, since pensions here are low — often around $130 CAD — and the cost of living has skyrocketed due to inflation and the war. Many seniors in Ukraine live in abject poverty; they’re certainly not frolicking in donated wealth.

He didn’t believe me. He knows that most news about Ukraine is all lies. Some of us, I gently replied, came to Ukraine to see the truth for ourselves; he asked if I was a “paid propagandist.” When I informed him that I actually took an unpaid leave, living off my own life’s savings, he decided it was suspicious that I could afford such an endeavour “on a writer’s salary,” then demanded I pass a litmus test of admitting that the March 2022 bombing of the Mariupol drama theatre was a “fake war crime.” As in, obviously fake, he stressed. As in, there were no civilians killed there.

At that point, I tapped out of the discussion: while my personal finances are, I assure you, quite underwhelming, I wasn’t in the mood to whip out my bank statements to a stranger. More than that, I realized there could be no productive discussion, because we had no point of agreement on basic reality from which to start.

What I’m saying is this: while the death toll of the Mariupol theatre bombing is not known with great certainty, to declare it “fake” in a literal sense — that no civilians died there — one has to believe that a multitude of organizations, some of which are competitors, conspired to fabricate reams of survivor testimony and visual evidence. That the New York Times, the Associated Press, Amnesty International and several other media outlets and human rights groups all agreed to make it up. (Even Russia doesn’t deny the attack happened; it just alleges Ukraine did it.) I don’t know how to find common ground with someone whose rejection of these sources is so total.

The catch here, of course, is that we do have to be critical of what we see in the media. We do have to be careful. Social media is awash in fakes and forgeries. In news media, even the most careful reporting can never be fully cleansed of bias, because it requires making choices. Which questions are asked, and which are never imagined; what facts are deemed important, versus which are discarded; which voices are heard and which, for whatever reason, don’t get the chance. Plus, the world’s a big place, and it’s hard to get a full picture. I’m sure there are many things I haven’t seen in Ukraine, that I don’t know I haven’t seen, which shapes how I perceive this country and the war too.

So we shouldn’t take everything we read as unassailable gospel. We should understand that at its best, news gives an incomplete window on the truth. Yet it seems to me that over the last couple of decades, and accelerating at a horrifying pace due to the nature of social media, healthy skepticism is being replaced by a more pernicious conviction: that everything in media is a fiction, that none of it is real, that the only voices we can trust are the ones telling us nothing is true, except what we see with our own eyes.

How does that depth of distrust take root? I have a guess. Because on those nights in Sloviansk, bombarded by Tweets screeching that the war I could hear from my bed is fake, I felt the first flutterings of doubt in my brain too. Not about the war, of course. It’s just that, the longer I spent immersed in messages that everything is a lie, the less sure I was that there’s any meaning at all left in truth.

— — —

In the end, these are some things I know to be true.

I know that the Earth is round, and the steel beams of the World Trade Centre didn’t have to melt, but rather weakened until they could not bear their immense pressure. I know that 12 people have walked on the Moon, and more may do so soon. I know that people in Kyiv eat Big Macs, and wake up a few hours later to the sound of explosions from missiles being shot down over their heads.

And I know that in a tiny village near Chasiv Yar, a short drive from the hell formerly known as Bakhmut, mortars and rockets fly high over tin roofs while children play in their yards and an old man named Vyacheslav lies on a dirty sheet, surrounded by pill bottles and empty tins of canned meat, choosing, in his way, to die in the one place he feels safe. I know that in Sloviansk, the trains arrive every day, ferrying some soldiers to the front and taking others away. I know that some of the men I saw disembarking will never come back that way again.

Above all, I know that people are mostly the same. We’re all trying to make sense of a world that’s too vast to fit into a single frame, a task made far more difficult in an era where we are constantly assailed by storms of information, battering at us from every direction, until we no longer know what to trust. We gotta try to hang on, though. Or else any hope of finding our way through together is lost.

What I’m Reading

I haven’t watched CNN in years, but I followed the blowback to its disastrous Trump town hall; The Atlantic’s long piece on the mistakes leading up to that moment is a scathing behind-the-scenes look, and an absolute must-read.

Researchers have found a link between some of the most severe forms of mental illness, and auto-immune conditions attacking the brain. A fascinating piece, on how asking new questions of old problems can lead to surprising answers.

This CBC investigation into a fundamentalist Christian sect seeking to “infiltrate (Canada’s) political system” is a wake-up call that we’re not immune from the kind of extremist political push that has so seized American politics.

One Picture, One Story

Behind my apartment in Sloviansk there was a little picnic table, shaded by spreading trees. The backyard seemed to me a paradise, an unkempt garden of delight, beautiful in how it grew untended. In the evenings, I liked to take my laptop out and just sit for a few hours, listening to the distant booms of outgoing shelling, writing poetry. It may sound strange, given the soundtrack, but I felt very lucky to be there.

At first, the little old ladies who live in the apartment building were suspicious of who I was. But one afternoon, one of them sat down at the picnic table, peering at me with curious eyes, and began to pepper me with rapid-fire questions in Russian. I managed to grasp just enough to answer the most basic: Yes, I’m renting apartment 14. No, I’m not a volunteer, I’m a journalist from Canada.

Her eyes grew wide. “Z Kanadi?” she exclaimed, delighted. I suspected that, in a tight-knit old apartment building such as this, having a temporary Canadian neighbour was a welcome bit of gossip.

One by one, the other grandmothers soon strolled up to join us. Each time a new face arrived, my first companion gleefully informed them of my origins — “Ona z Kanadi” — as I smiled back in awkward silence. My presence thus accepted, we spent several hours sitting comfortably together, punctuated by their insistent urges that I partake from their communal bag of sunflower seeds.

After that, the little old ladies always greeted me warmly, when I saw them in the garden. It was funny, I thought, how little we had in common. But you don’t need much: sometimes, a picnic table, a warm summer evening, and a bag of sunflower seeds is more than enough.