It was hot that June night in Sloviansk, summer 2023. Curfew fell, and then darkness. I was talking with Emma in the gazebo behind the former United Nations house that served as hub for her humanitarian charity, Road to Relief. The back gate rattled, and opened. We looked up to see the familiar face of Khrystyna, one of the NGO’s medics, trailed by two grinning soldiers.

I flashed Emma a concerned look. I was still new to the environment, then.

“Oh, they’re friends of hers,” Emma said.

Khrystyna settled at the long table, right beside Emma. I admired Khrystyna, though I did not know her well. She was kind, with a long, wistful face and gentle blue eyes; she would quietly help me with a word or two in Ukrainian, when she sensed I was stuck.

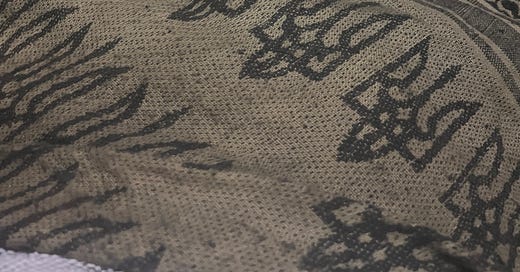

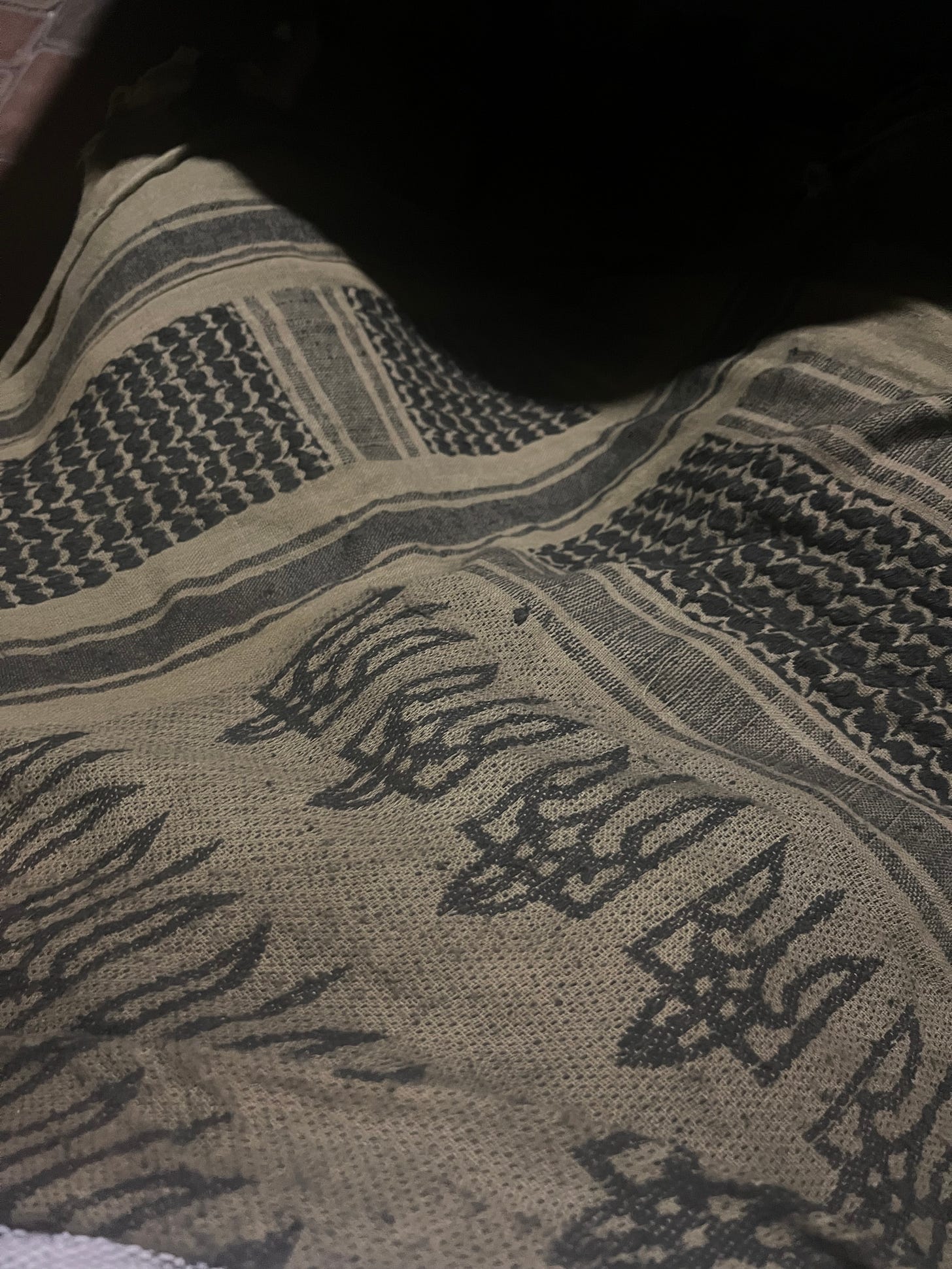

I turned my attention to the soldiers. They were a jovial pair, both middle-aged with close-cropped greying hair. One was stout with a broad, ruddy face; the other was tall and strikingly handsome. What drew my attention, though, was what he wore around his neck: an army-green keffiyeh, woven with the Ukrainian trident symbol. It looked much like one I owned from Hirbawi, I thought, in its construction.

“Where did you get that?” I exclaimed, as Khrystyna translated.

The soldier, without a moment’s hesitation, walked over to where I was sitting, squeezed behind my chair, and wrapped the scarf around my neck. Surprised, I protested the gift: “oh my gosh, thank you, but I can’t take this.”

He grinned and wrapped it tighter.

“Very beautiful,” he declared.

I turned to Khrystyna to plead my case. Tell them, I said. But she just shook her head with a knowing smile. Her blue doe-eyes twinkled.

“Just take it,” she said. “It’s like an honour for them.”

Emma, stressed by something with work, got up and flounced into the house. The rest of us sat awhile. The soldiers drank beer — banned in that region now, yet easy to get, if you know how — and chatted with Khrystyna in Russian, laughing at jokes of which I could glean just a fraction; but still they kept turning to me and winking, inviting me to share in the glow of company, if not a language.

War is strange, I thought. It destroys so much. Yet sometimes, it also creates.

Sometimes, I wonder what happened to the soldiers. I wonder if I’m the only person left, who was at that table that night. My Ukrainian veteran friend frowns when I mention this. “Don’t bury them before their time,” he says. True, true. But we all know what this war is like.

In the months after Emma and Tonko were killed, Khrystyna became a medic with Hospitallers, a volunteer battalion that evacuates wounded soldiers from the front. She moved in with my friend Nicholas, who’d adopted the calico as a favour to me.

Khrystyna’s dedication to the cause astonished me. When she was off rotation with Hospitallers, she filled their apartment with medical supplies that she’d fundraised for, that she packaged and shipped to other medical workers at the front. In the late summer, she helped out at a camp in the Carpathian Mountains, working with front-line refugee kids. All the time, it seemed, she was fundraising, organizing, gathering supplies; every cent and every ounce of energy she had went into saving lives.

This summer, Nicholas suggested that she and I should meet up sometime, just the two of us. Maybe, he thought, she could use some cocktails and girl chat. I loved the idea; I admired Khrystyna, and wanted to get to know her better. I texted her asking when she’d like to meet.

“Hi Melissa! Yes, with pleasure,” she replied. “I’m free tomorrow and after tomorrow definitely. Or up to you.”

I didn’t text her back. I can’t remember why not.

The last time I saw her, I was leaving Nicholas’s apartment after a friendly morning visit. She was just arriving back home, carrying boxes of medication and syringes. I was tired, and so headed for home; we gotta get that drink soon, I told her, and she eagerly agreed.

I need to take my own advice, about not missing these chances.

— — —

On the morning of my birthday, the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv closed after putting out an ominous warning about an impending “significant air attack.” Many other embassies soon followed suit.

The news sent a chill over Ukraine. What was different about this threat? The country gets attacked every day, yet this was the first time since early in the full-scale invasion that embassies had closed. It seemed a very bad sign.

That day, business in the capital went on as usual, but the air was thick with tension. An afternoon alarm sent some people flooding into the underground metro; a trio of explosions boomed as air defence took out a pair of hypersonic missiles.

Was that it? Was that why the embassies closed? It didn’t seem right; that sort of strike is not uncommon. That night, Ukraine went to an uneasy sleep, both relieved and afraid that nothing too bad had happened.

The next morning, many awoke to a fresh horror: a strike on the central Ukrainian city of Dnipro, of a kind nobody had ever seen before. For the first time in history a country had used a space-travelling missile in combat, firing a new type of weapon towards a city of nearly 1 million people.

In a speech hours later, Russian president Vladimir Putin named the new weapon as Oreshnik — or “hazel tree” in Russian. It was initially reported as an intercontinental ballistic missile; experts corrected that it was actually an intermediate-range missile, or IRBM. (Reuters has an excellent breakdown of the weapon, including videos of the Dnipro attack.) Putin boasted that nothing could stop it. (This may not be correct.)

In the hours after the strike, news and social media chatter was apocalyptic. But there are two things worth noting, if one wishes to keep a calm head.

The first is this: the missile wasn’t armed, even with conventional warheads. Video of the strike shows no impact explosions; Ukrainian officials reported minimal damage. The second thing to note: Russia did inform U.S. officials that they planned to launch the IRBM, as per a treaty designed to limit the risk of an accidental nuclear exchange. This explains the embassy closure.

Taken together, those two facts make it clear that while the Oreshnik attack was very much an escalation, it was primarily a public message. (The Moscow Times, which is based in the Netherlands and considered a foreign agent by the Russian government, reported this as well, based on discussions with government sources.)

The message was fear: “be afraid of what we can do to you.” The goal is for that fear to swell into public pressure — not just in Ukraine, but in the West — to capitulate.

Later that afternoon, the siren sounded again in Kyiv. One of the attack monitoring channels reported a launch from Kapustin Yar, where the Oreshnik had originated. I grabbed a bag and dashed for the metro, plunging deep underground where nothing can get us. The subway stations of Kyiv were designed to be nuclear bomb shelters.

It’s been a long time since people in Kyiv went to shelter when air sirens sounded; for the most part, life goes on. Bu that day, the subway was full. Everyone sat on the floor, or on folding chairs, hunched over their phones, hunting for information on what was coming towards us.

A short time later, the alert was lifted. False alarm, it turned out. “I apologize to those whom I scared,” someone who runs the attack monitoring channel wrote. “A difficult day. I went to treat my nerves.”

There is a word for factions who weaponize fear, to obtain what they want.

— — —

In Zaporizhzhia late last month, on a work trip for the Free Press. In the middle of an interview when my phone rings: it’s Nicholas. My blood runs cold. I abruptly stop the interview, and run off to take the call.

It’s never good when the phone rings here. It’s really never good. If it was good, it would’ve been a text.

— — —

Before you read this next part, I ask you to listen. The chants of Ukrainian Orthodox priests, have you heard them? A sound out of time and, if you close your eyes, even a little bit out of dimension.

Instruments are banned in Eastern Orthodox worship; only the voice is used to praise God. The language they use is not Ukrainian, but Church Slavonic, a tongue used only for liturgy. If you can — if you’re in a quiet place, or have headphones — please listen to this, as you read the last part of this newsletter.

If you can’t listen, then I want you to imagine voices. A solo call, a chorus response. Ethereal harmonies adorned by the jangling bells of the kadylo, the incense-burner that an Orthodox priest swings as he walks. Plaintive voices, voices of supplication. Voices smooth as moonlight on still water, echoing under the vault of the cathedral ceiling, rising to the rafters, to the sky, and onwards to heaven.

On this recording, there is also an occasional crackle of plastic. I apologize for this, but it’s part of the story. I was holding a bouquet of flowers in my arms. I tried very hard to stay still, but they spoke their own prayers through their wrapping.

— — —

She looked peaceful, in the end. Hands gently clasped, hair around her shoulders, a black coin-sized wound on her lip. Caskets are usually open in Ukraine, unless they aren’t. Khrystyna’s was open. The mortar that blasted into her makeshift ambulance — a retrofitted Nissan Pathfinder — didn’t do the kind of damage that would steal a chance for her loved ones — or the journalists who came — to have one last look.

The cathedral at St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery — rebuilt in 1999, after the original was destroyed by the Soviets — is beautiful, in the opulent way of Orthodox churches. Everything glows, gleams, glistens. Candles flicker, throwing their light on walls clad golden filigree and painted saints. It was built to inspire wonder, not sight lines. So many people fill the cathedral for Khrystyna’s funeral that we find ourselves squeezed in one of the vestibules, looking only at the columns that soar to the ceiling.

The priest swings the kadylo in front of him, and begins chanting. Tendrils of incense slip fragrant fingers between rows of bowed heads. We stand still, close our eyes, and just listen as they chant their hopes, committing Khrystyna’s soul to heaven.

The army-green keffiyeh is coiled around my neck.

I’ve never been to an open-casket funeral before. Neither have several of my foreign friends. (In the other funerals we’ve been to here, the caskets were closed.) In North America, we tend to look away from death. We don’t know how to face it.

The nurses at the hospital ask if we need one last visit with my dad, before they take him away. My brother goes. Two of my sisters. I stay in the hall. I can’t dad, I love you, I’m so sorry. You understand. I can’t bear to remember you this way.

“You don’t have to go up,” my friend Jonathan whispers.

My stomach wavers. I don’t want to go, but I can’t stay behind, either. I want to stand with my friends. I want to bear witness to what was done to Khrystyna, without a veil of distance. Her life didn’t end; it was ended. She didn’t pass away; she was murdered. Someone loaded that mortar. Someone found the range. Someone pushed that button. Someone wanted to kill the people in that makeshift ambulance, and they did.

The news talks about escalation. It should talk more about volition, about the moral rot that clings to all who decide to kill — not in defence, but in conquest. Not to save life, or protect it, but to expand, to seize, to claim.

I fall into step behind Jonathan. We join the long line of people slowly filing past her casket, pausing to touch her hand, or kiss her brow, or stroke the wood of the casket’s edge. When it’s my turn, I bow my head, glance at her once — just for a moment, just long enough — and kneel on the cold stone floor. I take the corner of the army-green keffiyeh, kiss it once, and hold it towards the placid tableaux of her body.

Thank you, Khrystyna. I will carry this in your memory.

It’s a damp, chilly morning in Kyiv. Mourners trickle out of the sanctuary and huddle in the courtyard, pausing to kneel again as her casket is lifted by an honour guard of other medics and carried out into the van that will drive her to the cemetery.

As we leave, another funeral procession comes in, men in military fatigues carrying the banners of their unit. There will probably be another funeral after theirs. This is war. You already know it. It is death, and only death. If you don’t look at it, you have not really seen it.

— — —

If you wish to donate to Hospitallers in honour of Mariya-Khrystyna Dvoinik — call-sign Alpaca — you can do so here. (For Canadians, scroll down to find info to donate by PayPal or credit card.)

— — —